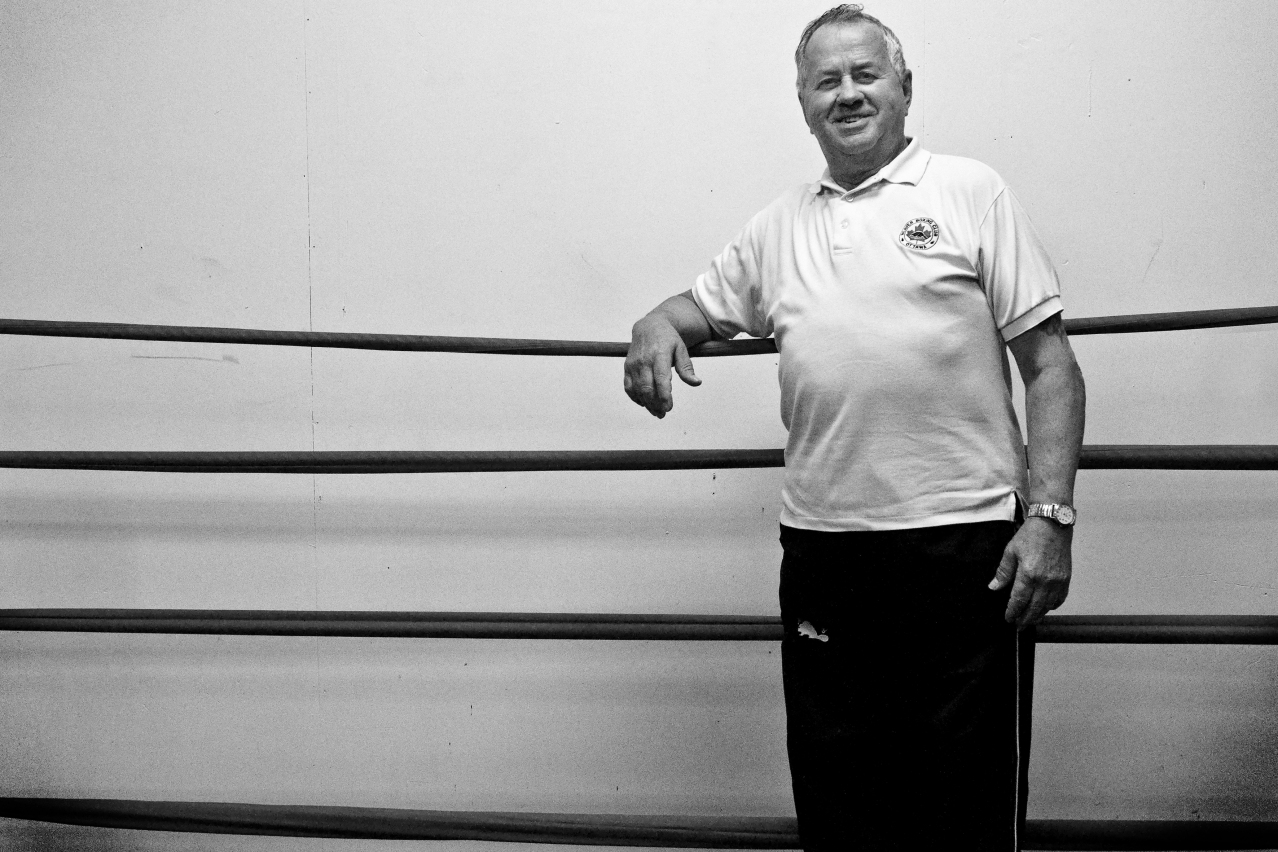

The Boxer – One In A Million

By Bruce Deachman

(Originally published July 25, 2010 in the Ottawa Citizen)

It cost Canadian authorities $25 to formally protest the ruling of the three Olympic judges, so you have to think they were sure the boy in their corner had won.

Joe Sandulo was only 17 and a 110-pound flyweight when he represented Canada at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, England — the first Games since Berlin played host a dozen years earlier. He fought one bout, against Burma’s Myo Thant Maung, and the judges ruled it a split decision.

“I thought I won,” Sandulo admits. “I was a bit disappointed in it, definitely. I thought I had the better of it.”

Although he lost on appeal, Sandulo looks back on the Games fondly. “It was a very high and great experience for me.

“Let’s face it,” he adds, “everybody, regardless of which sport you’re in, would like to be the best there is. I would have liked to have accomplished a bit more, but I took it as far as I could go, and was happy with what I achieved.”

His experience at the Olympics also didn’t hurt his boxing career back home, where he amassed 70 wins against just five losses, with promoters eager to include an Olympian on their fight card.

***

When you’re in the ring, this is the only thing that should be going through your head: winning.

“No matter who your opponent is, you want to be able to beat him. You want to be the best in the ring. You think about who you’re in against and what you’re going to be doing next,” says Sandulo.

“You’re not thinking about what you left at home or anything else. Your opponent is in front of you and you’ve got to focus on him 100 per cent. If you don’t, you’re just out of luck; you’re not going to win the fight.”

The youngest of four children, Joe Sandulo grew up on Parkdale Avenue and started boxing at the Beaver Boxing Club in 1946 when he was 14, following in one of his brothers’ footsteps. His daily routine then, he recalls, involved a lot of conditioning, something he still stresses for boxers today.

“Conditioning is No. 1,” he says. “I don’t care what sport you’re in, if you want to excel, you’ve got to be in condition.

“I used to run to school and run home from school,” he adds, “and then I’d run down to the Ottawa Boys and Girls club to work out.

“And then I’d take the bus home.”

He won the national championship when he was only 16 — the youngest Canadian ever to do so — and only a few weeks after his 17th birthday found himself aboard the Cunard ocean liner RMS Aquitania with Canada’s Olympic team.

He competed for only five years, however, joining the Canadian Forces as a cartographer in 1950, a career that lasted close to four decades.

He never turned his back on the sweet science, though. Over the years, he’s been an official, administrator, trainer and coach — helping two fistfuls of boxers, including Jill Perry, Ian Clyde, Samir Loati, Barry Dolan, Nora Daigle and Brian Brennan, become Canadian champions.

But Sandulo doesn’t measure success as a coach simply by the number of champions he’s nurtured. The club, he says, has also been a place where kids with problems at home or with the law have straightened out their lives.

“One individual — I don’t want to use his name — lived down in Lowertown and he was in quite a bit of trouble. But once he got into boxing, there was quite an improvement at home.

“He just called me up and thanked me for the time I spent with him, and this is going back a few years — he’s 50 or 52 now.

“It sort of touched me.”

Since 1975, Sandulo has been president of the same Beaver Boxing Club he trained at as a teen. The club has been without a home of its own since this winter, and currently operates out of the N-1 Thai Boxing Academy on Preston Street. He’s also coached Canadian national boxing teams at world championships, and for eight years was president of the Canada Cup international boxing tournament.

The trophies, ribbons, medals and framed photos that fill the basement rec room of his home in Pineglen, near Merivale and Slack roads, tell of his success, and, approaching 80, he still coaches three nights a week.

“The hardest thing is keeping the wife happy,” he says. Sandulo and his wife, Mary, were wed in 1952 and have three children. “A coach does a lot of time away from home, and if he hasn’t got the proper partner, it’s very, very difficult. There’s no money in it, but you do a lot of traveling, and leaving your loved one — who’s No. 1 — behind each time.”

Additionally, he says, a good coach needs a lot of patience. “You also have to be really dedicated to it. As an amateur coach, the only thing you get out of it is the self-satisfaction of seeing an individual accomplish their goal.”

That satisfaction may be the only thing he needs, though. “It makes you feel pretty damn good when you work with an individual and you see them coming up through the ranks, winning their first bout or winning the provincial championship or winning the national championship. It sort of gives you a little pat on the back and you say ‘What the hell. You’re doing something that’s worthwhile doing. Keep on doing it.’”